Searching for impact: How our Global Health & Development Fund fits into the development landscape

▲ Photo by Vis M. on Wikimedia Commons

Related articles

This is the second in a four-part series discussing our new Global Health & Development Fund and our approach to grant-making. The first post shares our rationale for launching the Fund.

The field of global health and development is huge. Each year, over $2.8 trillion is spent on development initiatives in low- and middle-income countries.1 Forty-two million children are vaccinated each year by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance,2 the Against Malaria Foundation has handed out over 100 million bed nets to date,3 and GiveDirectly alone has sent over $300 million in cash transfers to people in low-income countries.4 These efforts have helped reduce the number of people living in extreme poverty from 1.9 billion in 1990 to 650 million in 20185 and saved millions of lives.6

Given the scale of these numbers, it’s natural to wonder how Founders Pledge and its members can really make a difference. That’s the challenge we face as we develop our Global Health and Development Fund, launched earlier this month. To make sure we complement existing efforts, rather than duplicating or supplanting them, we began by seeking to understand the major players and trends in this space.

The funding landscape is broad and varied

Within the field of global health and development, there are literally thousands of different things a philanthropist might fund. Our job is to fish the absolute best funding opportunities out of this vast ocean. Thanks to our research on causes like women's empowerment and forced displacement, as well as the work of our research partner GiveWell, we have a strong understanding of how philanthropists can best fund the direct delivery of effective poverty reduction and preventive health programs. These programs increase the resources available to households living in poverty and reduce the risk of death from diseases like malnutrition and malaria, which kill hundreds of thousands of people each year.7 But there are many other interventions, especially those which affect development policies rather than programs, that we have so far been unable to cover in much depth.

Our job is made even more difficult because we are agnostic about the types of interventions we support. Rather than focusing on specific issues, we care primarily about how much an intervention improves somebody’s overall well-being. That means we’re open to funding traditional global development interventions like cash transfers or education programs, as well as less traditional programs like improving mental health or supporting evidence-informed decision-making by governments.

This cause-neutrality gives us more flexibility to find outstanding opportunities other funders haven’t taken. In order to work out where these opportunities are most likely to be, we’ve briefly surveyed the development finance ecosystem. The space has three main types of funders: domestic governments, official development assistance from high-income countries, and private philanthropists. Here, we discuss where and how money is spent in these sectors and the gaps that we think we can fill. We think the Global Health & Development Fund can achieve outsized impact by supporting both direct interventions with lots of room for more funding and neglected, higher-risk work in policy research, advocacy, and implementation support.

Domestic governments fund most development projects

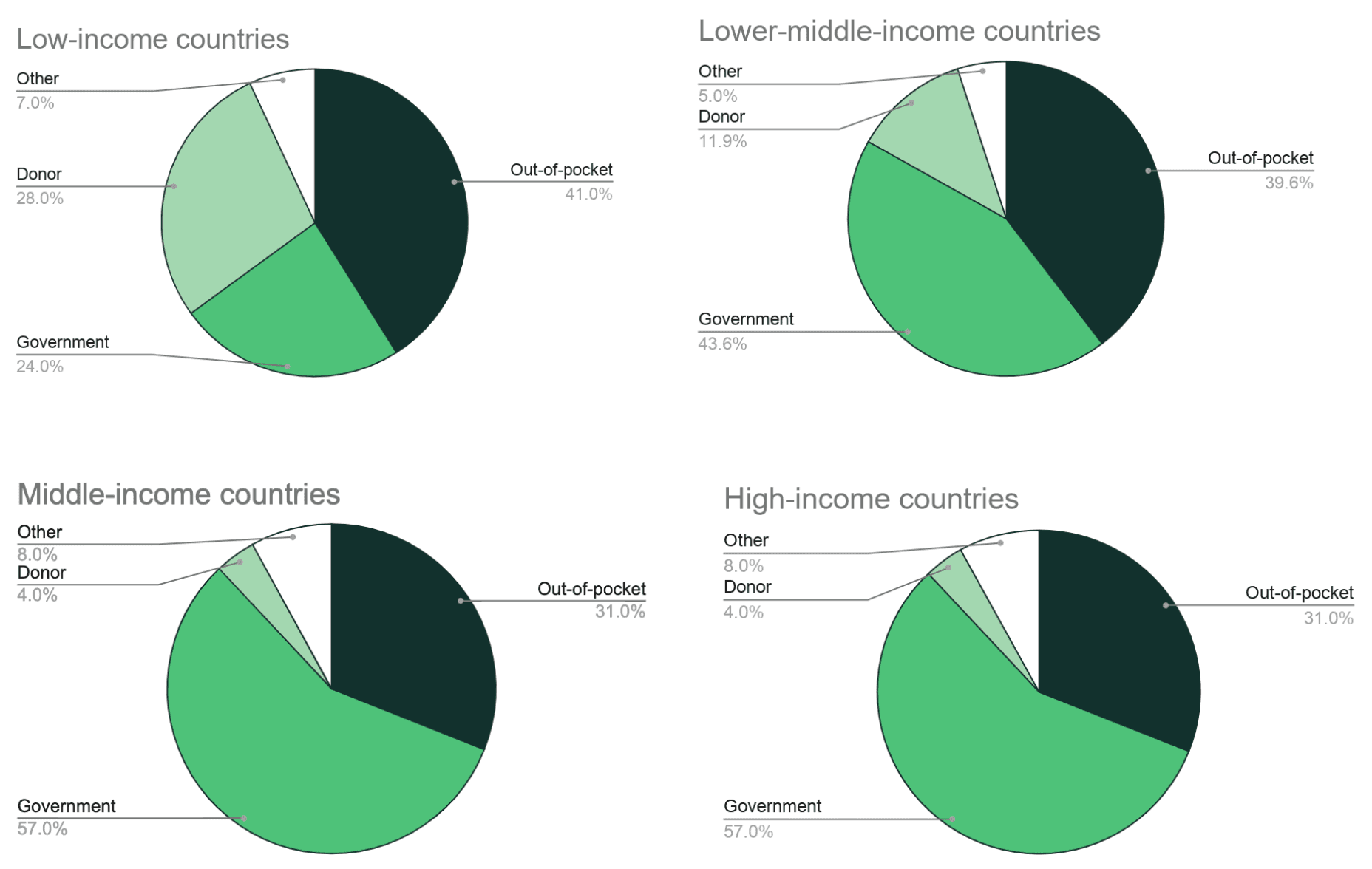

The vast majority of resources spent on tackling poverty come from governments in lower-income countries. In 2011, over 80 percent of the $2.8 trillion spent on financing development initiatives in low- and middle-income countries came from domestic government revenues.8 In 2017, government spending represented about 60 percent of total health expenditure around the world, although out-of-pocket spending by individuals is still the largest source of health funding in low-income countries.9

Figure 1. Share of health spending by source across country income groups

Source: Ke Xu et al., “Global Spending on Health: A World in Transition” (World Health Organization), Figure 1.7.

This represents a great opportunity for philanthropists. We think supporting organizations that advocate for more efficient use of government resources is one of the most promising areas for donors to achieve large-scale impact. We already recommend J-PAL’s Innovation in Government Initiative in this space, and are excited to look for more opportunities to help governments in lower-income countries implement policies that drive improved development outcomes at scale.

Supporting higher-risk opportunities for impact

Official development assistance (ODA) is “government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries.”10 In 2018, the 30 countries that make up the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee disbursed over $150 billion in net ODA. The chart below shows net ODA flows from the members of the Development Assistance Committee.11

Over 20 percent of ODA flows went to the African continent in 2018. Another 7.8 percent went to South and Central Asia, and 7 percent went to the Middle East. Much ODA passes through large organizations working within political constraints. Multilateral institutions, including the United Nations, the World Bank, and over 200 other institutions and funds, receive 30 to 40 percent of total ODA.12

Compared to ODA and domestic spending, private philanthropy for global development seems small. According to a 2018 OECD report, private philanthropy spends about $8 billion per year on development. Within this total, philanthropic giving for low- and middle-income countries is highly concentrated. Over 80 percent of total philanthropic giving from 2013-2015 was provided by only 20 foundations, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation alone contributed $11.6 billion, almost half of total giving during those years. The next largest contributions were made by the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, Dutch Postcode Lottery, and Ford Foundation, each of which granted between $600 million and $800 million to global development between 2013 and 2015.13 With so few actors playing such a large role in funding global development, activities that fall outside the interests of these foundations are likely to be overlooked.

While ODA and philanthropic funding together total at least $150 billion per year, it seems likely that these funders work within constraints that cause them to pass up valuable opportunities. For example, a large proportion of both ODA and philanthropic funding is risk-averse. A substantial amount of both ODA and donor funding, especially in the health sector, is channeled through large, well-known intermediary organizations like UNICEF and Rotary International.14 In addition, 67 percent of philanthropic funding for development went to middle-income countries like India, Nigeria and South Africa, potentially neglecting opportunities for impact in the poorest countries. We see a clear role for our Fund in supporting higher-risk opportunities for impact.

The role of the Global Health and Development Fund

With almost $3 trillion of development finance pouring into low- and middle-income countries every year, it’s natural to wonder how the additional contribution of a private donor can make a difference. Our review of the ecosystem has shown that there are important gaps, which Founders Pledge members are well-placed to fill. Domestic governments spend more than 10 times as much on development as OECD governments and private philanthropists combined; opportunities to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of this spending are highly leveraged. We also believe that ODA and philanthropic funders are constrained in important ways, leaving open good opportunities to fund higher-risk projects. We believe the best use of our funds will be a combination of the following types of activities and organizations:

- Expanding the direct implementation of programs that are supported by substantial, high-quality evidence and where funding is the main constraint stopping them from serving more eligible participants (examples include the Against Malaria Foundation and Helen Keller International’s Vitamin A Supplementation program, identified by our research partner GiveWell). We view these opportunities as comprising the “low-risk” segment of our grant portfolio.

- Conducting policy advocacy and technical assistance to encourage governments and other large-scale actors working in global health and development to implement more effective policies and programs. This segment of our grant-making will require substantial time investment to identify the most promising opportunities, but will likely uncover funding opportunities with the potential to generate larger positive impacts than the opportunities in the preceding category.

We see this Fund as an opportunity for the Founders Pledge community to support organizations or programs that may be less appealing to other funders, despite offering some of the best opportunities for donations to translate into impact. Our next post in this series will discuss this in more detail.

Learn more about the Fund and make a donation.

Notes

-

“In 2011, developing countries (excluding China and India, which are each treated as sui generis in the analysis below) mobilized around $2.8 trillion of development financing, of which $2.3 trillion was through the domestic revenue mobilization of their own governments.” Homi Kharas, “Financing for Development: International Financial Flows after 2015,” Brookings (blog), November 30, 1AD, https://www.brookings.edu/research/financing-for-development-international-financial-flows-after-2015/. ↩

-

“From 2000 through 2018, Gavi support contributed to the vaccination of more than 760 million unique children through routine immunization and to more than 960 million campaign immunizations.” (https://www.gavi.org/programmes-impact/our-impact/facts-and-figures) ↩

-

“The number of people in extreme poverty has fallen from nearly 1.9 billion in 1990 to about 650 million in 2018.” https://ourworldindata.org/extreme-poverty/. ↩

-

“The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that vaccination prevents 2-3 million deaths each year.2 However, while we are certain that vaccines have saved millions of lives, calculating a precise number is impossible. Also the quoted number from the WHO is in important ways a very low estimate.” https://ourworldindata.org/vaccination#vaccines-save-lives. ↩

-

“An estimated 250,000 to 500,000 vitamin A-deficient children become blind every year, half of them dying within 12 months of losing their sight.” World Health Organization, “Micronutrient Deficiencies,” WHO (World Health Organization), accessed October 11, 2020, https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/vad/en/. “The estimated number of malaria deaths stood at 405,000 in 2018, compared with 416,000 deaths in 2017.” “Malaria,” accessed October 11, 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria/. ↩

-

“In 2011, developing countries (excluding China and India, which are each treated as sui generis in the analysis below) mobilized around $2.8 trillion of development financing, of which $2.3 trillion was through the domestic revenue mobilization of their own governments.” Homi Kharas, “Financing for Development: International Financial Flows after 2015,” Brookings (blog), November 30, 1AD, https://www.brookings.edu/research/financing-for-development-international-financial-flows-after-2015/. ↩

-

“Government spending represented about 60% of global spending on health in 2017, up from 56% in 2000.” Ke Xu et al., “Global Spending on Health: A World in Transition” (World Health Organization), accessed October 13, 2020, https://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/health-expenditure-report-2019/en/. ↩

-

“Official Development Assistance (ODA),” accessed October 13, 2020, http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/official-development-assistance.htm. ↩

-

Note that the chart featured here presents ODA disbursements in constant 2017 USD, while the sector-specific statistics pulled from OECD.stat report ODA commitments in current prices, and the region-specific statistics pulled from OECD.stat report ODA disbursements in current prices. ↩

-

“The United Nations, the World Bank and other 200 multilateral agencies and global funds receive about one third of total ODA. When including earmarked funding provided to multilaterals, this goes up to two fifths. The scale at which the multilateral system is used reflects donors’ views of it as an important channel of development co-operation.” https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/multilateralaid.htm. ↩

-

OECD, “Private Philanthropy for Development,” The Development Dimension (OECD, March 23, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085190-en. ↩

-

OECD. ↩